ENVIRONMENT/AGRICULTURE: Vision system sorts tomato seedlings

More than 150 million tons of tomatoes are produced every year around the world. With seedlings costing €0.25, plant growers such as Westland Plantenkwekerij (WPK; Rotterdam, the Netherlands) must ensure that the seeds they receive from their suppliers will germinate as expected.

Seed suppliers provide germination percentage estimates by sampling batches of tomato seeds; however, plant growers must ensure that the seeds will flourish. If not, growers may overpay for the batches of seeds they receive. With companies like WPK growing several million plants per year, such losses can rapidly appreciate.

In the past, WPK employed 27 manual laborers to carry out the quality grading of tomato seedlings based on shape, color, and size, sorting them into different classes or rejecting them as unacceptable.

Tasked with automating this procedure, Rick van de Zedde, business development manager at Wageningen UR–Food and Biobased Research (FBR; Wageningen, the Netherlands;www.fbr.wur.nl), understood that these subjective classification methods were unacceptable. The ideas were based on the PhD project of Nicole Koenderink (FBR) and further developed within the MARVIN project, financed by a consortium of 13 breeding and plant grower companies and the Dutch government.

Within their contract research organization based at the Wageningen University & Research Centre (Wageningen, the Netherlands;www.wur.nl), van de Zedde and his colleagues have been developing vision applications in the agrifood industry for more than 20 years. In this project, they studied how numerous growers evaluate their tomato seedlings. Although multiple characteristics such as shape and color were evaluated by the growers, it became clear that the seedling sorting process could be robustly automated by measuring the mass of each seedling.

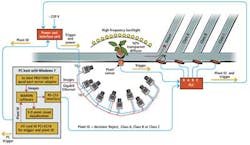

FBR designed the machine-vision system (see Fig. 1), and Flier Systems (Barendrecht, the Netherlands;www.fliersystems.nl) currently builds the machine.

Now installed at WPK's facility in Made, the Netherlands, the machine is capable of sorting tomato seedlings at a rate of 18,000/hr. According to Erik van der Arend, owner and director of WPK, the current version of the system sorts seedlings on the basis of the plant's biomass; it will eventually be upgraded to sort plants based on multiple characteristics such as the plant's shape, size of the leaves, and defects in shape or color.

In the WPK facility, seeds are automatically planted into trays each containing an array of 12 × 20 pots. After a 12-day germination period, these trays are then manually transferred onto a conveyor that feeds them into a pick-and-place machine. This is used to separate each pot 10 cm apart onto the conveyor of the machine-vision system (see Fig. 2).

As each pot enters the vision station, an optical switch triggers the presence of the plant. Interfaced to aprogrammable logic controller (PLC), the switch is also interfaced to an NI PCI-6518 digital I/O card from National Instruments (Austin, TX, USA) that is in turn used to trigger 10 acA1300-30gm 1296 × 966-pixel monochrome Gigabit Ethernet cameras from Basler (Ahrensburg, Germany), each fitted with a 25-mm Fujinon lens from Fujifilm (Wayne, NJ, USA). The images are transferred over the Gigabit Ethernet interface to a host PC that incorporates three Intel PRO/1000 PT quad-port server adapter cards.

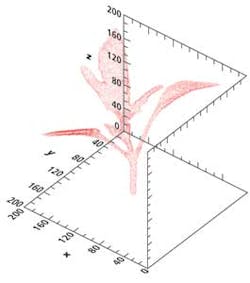

"Because of the relatively complex and nonuniform nature of the seedling plants," says van de Zedde, "ten cameras were required to properly recreate a three-dimensional model of the plants. And still our software is able to generate a 3-D model and calculate the biomass within 25 msec per seedling."

To calibrate these cameras, a flat checkerboard pattern is used in conjunction with a modifiedstereo-vision calibration algorithm available in the HALCON software package from MVTec Software (Munich, Germany; www.mvtec.com).

Because plants are illuminated by a high-frequency fluorescent backlight, the 10 captured images provide multiple views of the seedlings under inspection from different viewpoints. By subtracting the background from each of these images, a silhouette of the plant at different viewpoints can be created.

Then by using a technique known as Space Carving, a 3-D rendering of the plant can be created (see Fig. 3, and "A Theory of Shape by Space Carving";http://bit.ly/ImkfC3). Using this method, the biomass of each plant can be computed and the data used to classify each plant.

In the system deployed at WPK, plants are classified into four categories based on the volume, i.e., the biomass of the seedling. Based on the average size of a batch, the end user can adjust the boundaries per category. This results in first-, second-, and third-class seedlings and rejects (too small/ nongerminated).

The automated classification results from the PC are transferred to a PLC, which triggers a number of actuators to move each plant onto a particular conveyor depending on the classification result.

At present, FBR's van de Zedde is installing the next machine at a breeder and is upgrading the vision system to sort seedlings based on other plant characteristics, including color. "But the productivity gain in the quality of sorting is already huge," says WPK's van der Arend, "since our investment in this machine will be recovered within four years." (To see a video of the system, visithttp://greenvision.wur.nl/.)