Vision helps dairy spot slack cheese bags

Neil Flood and Bruce Bailey

Cheese making is a process that has been practiced for so long that that no-one can be sure where it originated. What is certain, however, is that early cheese makers would be unlikely to recognize today's highly automated processes which enable cheese to be produced in volumes that would have been unheard of years ago.

At UK-based cheese maker Dairy Crest (Camelford, UK; www.dairycrest.co.uk) for example, over 48,000 tonnes of cheddar cheese are produced per year, 80% of the output being the company's well-known Cathedral City brand.

To produce cheese in such high volume, up to two million tons of milk is delivered to the facility each day in tankers and pumped into storage silos. Next, it is pasteurized to kill bacteria. The milk is then transferred into curd making vats where solid curds are separated from liquid whey.

The curd/whey mixture from the curd making tanks is pumped to a Tetra Tebel (Wrexham, UK; www.tetrapak.com) Alfomatic machine where the whey is drained off, while the curd begins matting and fusing. After the curd has been milled to uniformly sized chips and salted, it is transported by vacuum to a block former. Here, the weight of the curd under vacuum compresses it into blocks after which they are automatically ejected into open-ended plastic bags.

To ensure the consistency of the blocks, the open ended bags are transported along a conveyor and weighed to ensure that they are 20kg. The bags are then carried to an auto gusseting machine where the open end of the bag containing the cheese block is folded in preparation for the sealing process.

Vacuuming and heat sealing the 20kg packs of cheese is a critical next step in the cheese making process. It prevents any air leaking into the bags of cheese prior to packaging and shipment to Dairy Crest's Nuneaton, UK storage facility, where the cheese blocks mature for between 12 to 36 months (Figure 1).

Vision checks cheese

To ensure the effectiveness of the vacuum and heat sealing processes, AutoCoding Systems (Sutton Weaver, UK; www.autocodingsystems.com) and Dairy Crest worked together to develop an automated vision-based system which can analyze, identify and reject any packs of 20kg blocks of so-called "slack" cheese bags which have not been sealed correctly.

With over 150 tonnes of cheese going along the line each day, the vision system was required to identify any vacuum failures in the packs of cheese as they passed though it on a conveyor at a rate of 10 blocks per minute. The inspection process is critical because even a small percentage of cheese blocks with broken seals would result in mould growth during the maturation period, and the resulting cost of recovering any contaminated cheese would be significant.

To determine how a vision system might identify the differences between a bag containing cheese that had been sealed effectively and one that was leaking, the surface of representative bags of cheese with good and faulty seals was analyzed.

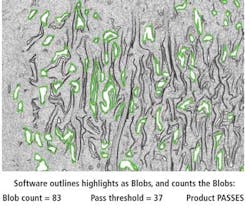

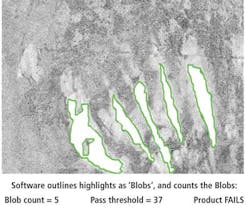

During that exercise, it was observed that the surface of the cheese bags demonstrated different reflective characteristics depending on whether they had been sealed correctly. When a good seal is made, the plastic bag is wrapped tightly over the uneven surface of the block of cheese and light reflects from numerous peaks of the plastic wrap (Figure 2a). On a bag with a leak, the plastic wrap is raised from the block, resulting in a uniform reflection of light from a limited number of peaks (Figure 2b).

Hence it was determined that if the vision-based inspection system could capture images of the reflected light from an area within a fixed boundary on the top of the cheese and count the number of peaks of a certain size and intensity, it would be possible to ascertain whether the vacuum sealing process had been effective.

Because the Dairy Crest plant produces a number of cheeses, packs containing different cheeses were examined to discover if one set of size and intensity parameters would be sufficient for the vision system to determine the integrity of the seals on all the varieties of cheese. The result of that exercise led the engineers to conclude that just two sets of parameters would be adequate.

Hardware and software

The vision system developed by Auto Coding Systems comprises two stainless-steel IP67 rated cabinets. The first houses the camera and lighting system, while the second contains a computer system that processes the images from the camera and transfers data to the Dairy Crest main server (Figure 3).

The camera chosen to image the packs of cheese was a 1024 x 768 In-sight 5401 camera from Cognex (Natick, MA, USA; www.cognex.com) fitted with a C mount lens with a 25mm focal length from Tamron (Saitama, Japan; www.tamron.com). Mounted 2.5ft from the surface of the cheese packs, it captures images of the top surface of the cheese bags through a circular aperture in a Model 10 high-frequency circular fluorescent light from Coherent (Santa Clara, CA; USA; www.coherent.com) positioned six inches below the camera (Figure 4).

On the production line, blocks of cheese are carried down a conveyor into the vision inspection station. Upon entering the system, an opto-reflective sensor from IFM Electronic (Hampton, UK; www.ifm.com) triggers the Insight 5401 camera which captures an 8 x 10 in image of the top surface of the pack of cheese. Image data from the sensor is then transferred over an In-Sight Ethernet network to a 1.6GHz personal computer running the Cognex In-Sight Explorer 4.0 software.

During the commissioning process, the In-Sight Explorer 4.0 software was used to configure the operation of the vision camera from the PC and to capture images of the bags of cheese. Cognex' associated Easybuilder software - with its drag and drop library of image processing tools - was then used to build the image processing application, obviating the need to write custom software.

To determine whether the packs of cheese had a faulty seal, an area find and blob analysis tool was chosen to process the images from the top of the packs of cheese. More specifically, the area find blob analysis software enabled the size of the patches of reflected light and their intensity to be determined.

By constraining both the size of the blobs that were detected and their light intensity range to within certain tolerances, it was discovered that the blob analysis tool could be deployed to highlight only specific key areas where the light had reflected off peaks on the surface of the plastic wrapping the cheese.

Having identified the blobs in the image that fell within those tolerances, a tool in the In-Sight Explorer Easybuilder software library was deployed to count the number of blobs in the image. After an experimental trial and error process, it was determined that a minimum of 37 blobs per image with a predetermined size and intensity would indicate that the vacuum sealing process had been successful (Figure 5a). Any less and the cheese pack was deemed to have been sealed incorrectly (Figures 5b).

Rejection and acceptance

Should the vision software identify that the image contains less than the prerequisite number of blobs, a digital trigger is sent from the PC in the vision system to a Micrologix PLC from Allen Bradley (Milwaukee, WI, USA; http://ab.rockwellautomation.com that sequences the operation of the conveyor carrying the cheese on the line.

As the cheese with the faulty seal exits the vision inspection station, its presence is detected by a second IFM laser sensor. The PLC then activates a bypass conveyor which lifts the faulty block from the line and transfers it down a side conveyor (Figure 6).

If a different variety of cheese is produced, the system can be reconfigured by selecting the new job containing the alternative blob size and intensity parameters from the In-Sight Explorer software.

While the potentially incorrectly sealed cheese is manually inspected by an operator, cheese that has been sealed correctly continues down the conveyor to be weighed a second time and labeled. Individual 25kg blocks of cheese are then packed into cardboard boxes after which they are labeled with a barcode.

Because the cheese is still at a relatively warm 30 degrees C, it is rapidly chilled overnight to 8 degrees C in a refrigerated store after which it is picked off a conveyor and stacked into pallets by a robot palletizer. Lastly, the pallet is wrapped and labeled before being transported to the Dairy Crest Nuneaton cheese store where it can reside for 12-36 months depending on the recipe and strength of flavor required.

Analyzing data

Aside from its ability to identify and reject packs of cheese with faulty seals, the vision system transfers images and statistical data from the inspection process to a server at the Dairy crest facility over an EDS-G205/G308 Ethernet switch from Moxa (Brea, CA, USA; www.moxa.com). There, manufacturing data is further processed by Autocoding Systems' custom Shoplogix software to generate a suite of reports.

Using the data produced from the vision software, the reports provide a statistical analysis of the total number of blocks that pass through the system, the number of seal failures each day and the time of day they occurred. By analyzing the data, engineering staff at Dairy Crest can determine whether there are any potential issues with either the auto gusseting or the vacuum sealing systems.

A catastrophic failure, for example, in which no blobs are found in the images of the packs of cheese, could indicate that the auto gusseting machine is not folding the flaps on the packs correctly. If blobs are found in the images, but if their numbers are lower than the predefined amount, it may signify that the sealer is not producing a high enough vacuum to seal the packs adequately.

The vision system paid back the initial capital outlay made by Dairy Crest within three months. Reports back from the company's Nuneaton storage facility, where blocks of cheese are repackaged into smaller quantities for sale in supermarkets, indicate that cost savings may be as high as £30,000 per month due to the decrease in the quantity of cheese required to be reworked.

Neil Flood and Bruce Bailey, Automation Engineers, Dairy Crest Davidstow Creamery, Camelford, Cornwall, UK

Company Info

Allen Bradley

Milwaukee, WI, USA

http://ab.rockwellautomation.com

AutoCoding Systems

Sutton Weaver, UK

www.autocodingsystems.com

Coherent

Santa Clara, CA, USA

www.coherent.com

Cognex

Natick, MA, USA

www.cognex.com

Dairy Crest Davidstow Creamery

Camelford, Cornwall, UK

www.dairycrest.co.uk

IFM Electronic

Hampton, UK

www.ifm.com

Moxa

Brea, CA, USA

www.moxa.com

Tamron

Saitama, Japan

www.tamron.com

Tetra Tebel

Wrexham, UK

www.tetrapak.com

Vision Systems Articles Archives