Automotive image-sensor business moves forward

By Tom Hausken

The potential applications for image sensors in vehicles are growing, with estimates that someday there will be from five to 20 cameras in cars, used in a mix of machine- and human-vision applications (see figure on this page). But what is often missed is that the automakers and the customers are not enamored with imaging. They spend more time thinking about things like styling, handling, fuel efficiency, new wireless services, and, of course, price.

Applications for imaging in automobiles include assistance in blind-spot viewing, lane-departure warning systems, and automatic headlight dimming. Rear, corner, and blind-spot viewing systems are the most common use of cameras in cars today. They are found in the Toyota Prius and as an option in Lexus models, where a back-up camera provides another perspective for the driver. Rear- and corner-view cameras have also been installed on cars in Japan as an aftermarket item.

Blind-spot cameras are also very promising to provide a warning signal to the driver using machine vision. Blind-spot detection has been offered on some Volvo models since 2005 in Europe and since 2006 in the USA

An effective way to use machine vision with input from other operations, such as turn signals, is to provide a warning to the driver if the car seems to stray out of its lane. It appeared as far back as 1999 in Japan and since 2000 in the USA on some commercial trucks. There will likely be more demand for this function from long-distance drivers in the USA than from Europe or Asia, because US roads can stretch many miles without interruption. In Europe and Asia, vehicles are used much more for busy city streets, where lane-departure systems are less effective.

Automatic headlight-dimming systems are now being installed in some General Motors, DaimlerChrysler, and BMW cars. These vehicles have the Gentex Smart Beam system, which uses an image sensor from Micron (Boise, ID, USA; www.micron.com) to detect an oncoming car and automatically dim the headlights.

Another use for imaging in automobiles is video-based event recorders. This is essentially a video “black box” to record an event in case of a crash-gathering data on liability and safety. The concept is catching on as an aftermarket item for taxis, commercial trucks, and celebrities in Japan. They also have been used for several years in commercial trucking fleets in the USA. There are regulatory efforts worldwide to require more event recording in cars, and these could speed deployment of video-based recorders.

In addition, several companies are developing driver alertness-monitoring systems for commercial systems. Toyota designed a system for a Lexus model in 2006.

The use of optical imaging to detect other cars, pedestrians, or obstacles and to decelerate or provide a warning is another use of imaging for this market segment. Longer term, the aim is to use wireless communication to allow cars to “platoon” closely together. The systems in production are mainly based on radar, lidar, or ultrasound, not imaging, but there are systems being developed that are based on optical and infrared imaging, most notably by Suzuki and Subaru. However, it is a big step from blind-spot detection to collision avoidance, especially if the operation is to go beyond a warning to intervention. This is a much less mature and less promising application for imaging.

Night-vision systems project an image onto the dashboard for the driver, using near-IR CCDs or far-IR arrays. Of all the applications, this one seems to capture the most attention in the press. Unfortunately, the systems do not work in fog or heavy snow, and there have been complaints that people have difficulty adjusting to the image.

The option first appeared as early as 2000 in the Cadillac Coupe de Ville and more recently in several other models. However, sales of the option so far have not been promising. It was dropped from the Cadillac and from RVs made by Fleetwood Enterprises because of low market interest. Meanwhile, Chrysler has decided that the timing is not right for introduction into its Jeep Cherokee models.

Another application, air-bag occupant sensors, generated a great deal of excitement a few years ago, but there are now less-expensive alternatives. Several companies are developing imaging solutions, but this application no longer seems as promising.

Airbag example

The million-dollar question in automotive applications is not only what will happen, but when? The airbag serves as a useful example to understand how long a rollout can take. Mercedes Benz first developed airbags as far back as 1967, but the early adopters dropped the technology in the 1970s. Mercedes reintroduced the airbag in 1980 as an option, and Porsche offered it as standard equipment in 1987, followed by Chrysler in 1988. Dual airbags became mandatory in the USA in 1998.

Thus, the airbag, which once seemed like an overnight sensation, took 20 years from development to large-scale rollout. Even now, 40 years later, not all vehicles are equipped with airbags.

The airbag is perhaps an early and atypical example of implementing safety technology in automobiles. Today the rollout would be more rapid. And, the imaging applications being considered today are already many years along in development and as many as 15 years since the concept phase. But it is important to appreciate the time scales in which the auto industry operates.

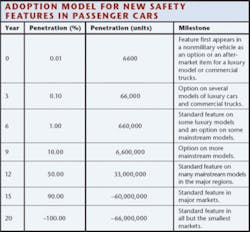

The table on p. 18 suggests a possible rollout for a similar new feature, not considering the effect of government regulations that may accelerate or decelerate adoption. Some new imaging features are about six years along in this penetration cycle, with several years left to go before the volumes reach a scale that rivals consumer products.

Government regulation can play a pivotal role here, but it can be an example of “watch out what you wish for.” A mandate can accelerate adoption of a new product and relieve the automakers from some legal liability for the feature if it fails. But, while car owners may appreciate the mandated features, they usually don’t want to pay extra for mandated features. So, there is less of a profit margin for the automakers. And, if the feature adds significantly to the price of the car, it can even dampen car sales. It may still be good for the camera vendor, though, since development costs can be paid off more quickly if the adoption is accelerated.

Product forecast

With so many unknowns, the automotive image-sensor market remains speculative. That is, some of the applications are finally in production, but the real winners cannot be known until they are fully proven in the marketplace. Complicating the forecast further, several features may one day share a single camera, so it may not be accurate to add up the adoption of each application in isolation.

The target price for the image sensor in a typical application, in large production volumes, is about $5. But, add to this the cost of optics and image processing, and it is hard at today’s volumes to get the price of an entire subsystem below $100. The specific prices vary, of course; infrared imaging is much more expensive than blind-spot detection. The more expensive features can cost the car owner $500 to $2000.

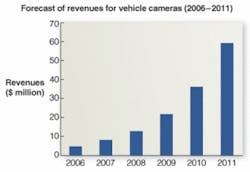

At Stratgies Unlimited, we expect unit growth to ramp rapidly from well below 1 million units in 2007 to greater than 8 million in 2011. Even with chip prices falling at 15% per year, this would yield revenue growth of an astonishing 65% through the period (see figure on p. 16). While the total revenues will still be small compared to camera phones or security cameras, they will be quickly approaching the size of the machine-vision segment. This phenomenal growth is just the beginning. If only 60% of today’s annual production (about 70 million vehicles) were installed with just five image sensors per vehicle, at $5 per image sensor, the market would be over $1 billion.

Automakers in control

Automakers are notoriously demanding of their suppliers. The tier 1 suppliers with imaging subsystems are companies such as Aisin Seiki, Bosch, Continental, Delphi, Denso, Magna, Omron, Siemens VDO, TRW, Valeo, and Visteon. There are also several tier 2 and aftermarket suppliers that are developing products in this area. These suppliers, in turn, put intense pressure on their suppliers (such as the chip makers) to meet specifications and price targets.

The technical specifications are daunting. The camera generally must operate from about -40˚C to +85˚C, with storage temperatures up to 125˚C. The dynamic range may need to be as much as 110 dB, for providing contrast ranging from sunlight to darkness. While the pixel counts can be submegapixel, the frame rates should be at least 25 frames/s for video images for humans. Most important, however, is that it is not enough that the image sensor works. The system has to work in a range of situations, and the system, including image and signal processing, can be very complex.

The customer view today is that CMOS arrays can better meet the expected performance, compared to CCDs, although CCDs have been used in automotive imaging. Notwithstanding the claims of the CMOS manufacturers, the supply of sufficient quality CMOS arrays has been inconsistent. Yet the customers believe that the quality will improve over time. Their suppliers must demonstrate that they can support the product for years to come. This culture trickles down the supply chain and favors established companies with deep pockets, or specialty manufacturers that are known to the automakers and their suppliers.

The customers also insist on second sources. A supplier that makes it into a new vehicle design will likely find that the automaker will demand a second source after about three years, if not sooner. The second source is not required merely to secure the supply chain. The automaker will use them as competitors to drive the price down even more.

Whoever wins some of the image-sensor business will have a demanding but steady automotive-industry customer for many years. The auto industry is relentless in the pressure it puts on its suppliers. But it also creates a barrier to entry for startup or inexperienced suppliers, helping those who make it inside.

TOM HAUSKEN is director of components practice at Strategies Unlimited, Mountain View, CA, USA; www.strategies-u.com.