Many of the machine vision systems used in industrial applications employ well known image processing algorithms to discriminate between good and bad parts. Algorithms such as thresholding, blob analysis and edge detection, for example, can be found in every machine vision software vendor's toolbox since they can be used in numerous applications to solve a relatively large number of imaging tasks.

To determine whether a part is good or bad, features such as color, length and area are extracted and compared with known good data. In this way, the vision system can, to an acceptable degree, be used to accept good parts and reject bad parts.

Uncontrolled environments

While these systems are effective in such applications, they are less useful in applications where there may be uncontrolled lighting or for sorting objects (such as fruits and vegetables) where the object's parameters are highly variable. To determine whether a particular fruit is ripe or not, it may not be possible to simply threshold the RGB data contained in a color image since statistically, an amount of statistically acceptable fruit (true positives) may be rejected and vice versa.

In such applications, image classifiers can be used to maximize the number of true positives while minimizing the number of false positives. Unlike a classically-designed vision system, however, where lighting is well defined, high contrast images can be obtained and measured image data can be compared with a known good part, image classification of natural objects is a more intractable task.

To perform this task with classifiers, often hundreds or thousands of examples must be presented to the vision system. However, as Dr. Pavel Paclik, Founder and Director of PR Sys Design (Delft, The Netherlands; www.perclass.com) points out, the old computer adage "garbage in, garbage out" hold particularly true when developing such machine learning systems since less, better-labeled data will result in a system more effective than one where a large number of badly-labeled data is presented to the classifier.

Indeed, in building such systems, it may be that the data presented to the system is not sufficient to classify the part. In fruit sorting for example, color histograms of RGB data may be presented to a classifier. However, these might not contain enough information to properly classify the fruit even though numerous types of classifiers may be tested on the data.

This, says, Paclik, leads to a "chicken and egg situation", where the use of classifiers must be used to determine whether an object can be classified using the data gathered by the imaging system. In the case of fruit sorting, for example, it may be that simple RGB data is not good enough and the use of multi-spectral data and the correlation between them may be more useful. However, only until a classifier is used, will this become apparent. Which classifier to use for a specific task is also important since choosing the correct one may lead to a more robust, accurate or faster implementations.

Learning techniques

Image classification may be performed using supervised, unsupervised or semi-supervised learning techniques. In supervised learning, the system is presented with numerous examples of images that must be manually labeled. Using this training data, a learned model is then generated and used to predict the features of unknown images. Such traditional supervised learning techniques can use either generative or discriminative models to perform this task.

In generative models, the joint distribution of images and labels is modeled and the class value for an unknown image computed. To compute this value, classifiers such as naïve Bayes classifiers and Gaussian mixture models can be used. In discriminative models, the conditional probability distribution of images and labels is modeled and classifiers using support vector machines (SVMs) or linear discriminant analysis and the related Fisher's linear discriminant are used to class unknown images.

Both generative and discriminative methods have their own advantages and disadvantages for image classification tasks as Ilkay Ulusoy and Christopher M. Bishop point out in their paper "Generative Versus Discriminative Methods for Object Recognition" (http://bit.ly/13D5gQx). While discriminative models may be very fast, for example, generative models provide high classification accuracy.

While supervised learning techniques require knowledgeable operators to train large image data sets, such experts are often unavailable to perform this task. In such cases, unsupervised learning methods can be used.

"Although it may seem somewhat mysterious to imagine what a machine could possibly learn given that it doesn't get any feedback from its environment," says Zoubin Ghahramani in his paper "Unsupervised Learning" (http://bit.ly/1J9lgtA) "it is possible to find patterns in image data using probabilistic techniques."

Unsupervised learning systems find patterns of values in the image data and build a probabilistic model or models from multiple unknown images. "Unsupervised techniques are useful to identify sub-structures of the problem such as sub-types of defects or product varieties. By interpreting the clustering results, an expert may understand the problem better and develop a more accurate supervised classifier," says Paclik.

In some cases, however, the data clusters generated by unsupervised learning systems may not be accurate. In such cases, semi-supervised learning techniques can be used that incorporate labeled data to reduce the amount of images that need to be trained by an operator while improving the accuracy of unsupervised clustering.

Application dependent

Choosing which classifier to use for any particular task is heavily application dependent and thus a number of different classifiers may need to be tested before the optimal solution can be found. For this reason, software companies offer a number of different types of classifiers which developers can use in their application.

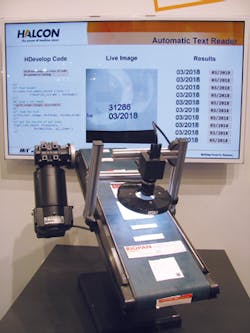

In its HALCON software package, for example, MVTec Software (Munich, Germany; www.mvtec.com) offers classifiers that use neural nets, SVMs, Gaussian mixture models (GMM) and k-nearest neighbors (k-NN). At last year's VISION show in Stuttgart, Germany MVTec showed how the neural network classifier could be used in optical character recognition. After presenting the system with a database of single character fonts of different sizes, the multi-layer perceptron (MLP) network was then presented with unknown characters on various business cards (Figure 1). If these characters on the unknown cards were of a high enough font size and characters could be properly segmented, the system was capable of recognizing the font with relatively high accuracy.

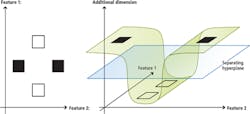

In the company's "Classification Solution Guide" (http://bit.ly/1GyzZw1), the theory behind these classifiers explained and numerous examples of how they can be used are given. In one example, the classification guide shows how SVMs can be used to construct a hyper-plane that can be used for classification purposes (Figure 2). Here, classes that are not linearly separable can be separated by using an SVM to transform the feature space into a space of higher dimension, so that the features become linearly separable. To aid the developer in choosing which features need to be used to create an accurate classifier, MVTec has also developed an automatic feature selection tool to automatically choose the best feature set used when building a classifier.

Stemmer Imaging (Puchheim, Germany; www.stemmerimaging.com) also uses an implementation of SVMs in its Common Vision Blox (CVB) Manto software. Using the software, developers do not need to select relevant features in an image since the software uses an image filtering technique during the training process to extract the appropriate information from trained images, according to Stemmer.

Automatic feature finding is also part of the SmartLearn multi-step classifier for surface inspection from Cognex (Natick, MA, USA; www.cognex.com. Here, a rule-learning classifier automatically finds a set of defect object features and learns rules based on a few set of feature values that uniquely describe the object. When defects cannot easily be distinguished based on a few unique features, a statistical classifier can be used. When the feature values of different groups significantly overlap, an SVM can be used to generate a multidimensional feature space to isolate different defect groups.

Perhaps one of the most comprehensive software toolkits for developing and testing different types of classifiers is PR Sys Design's perClass software. Offering a range of classifiers such as k-Nearest Neighbor (k-NN), neural networks, Random Forests, and SVMs, the software is a Matlab-based toolbox that allows developers to interactively work with data, choose the best features within the data for image classification, train the numerous types of classifiers and optimize their performance.

To date, the classifiers offered by PR Sys Design have been used in numerous applications including classification of defects in food, segmenting bones in medical scans, rock sorting, segmenting cell structures in molecular biology and classification of prostate cancer in ultrasound images. In the latter application, Dr. Dror Nir, CEO of the now defunct Advanced Medical Diagnostics (Waterloo, Belgium) used a perClass k-NN classifier to detect abnormalities in ultrasound data that are then marked in color as areas suspected of being tumorous (Figure 3).

Cascaded classifiers

However, as PR Sys Design's Paclik explains, many problems are rarely solved with a single classifier. For this reason, complex problems using multiple data sets can be split into several simpler problems and different extracted features used with multiple, cascaded classifiers. However, choosing which classifiers to use in machine learning systems represents only 20% of the engineering task, according to Paclik. Rather, the task of discovering which data is best suited for training the system and how to interpret the results to understand why such a classification system may fail and why is more time consuming.

Even when such systems have been optimized, in many applications - such as fruit sorting - they can never be 100% accurate. However, in such applications, this may not matter since an acceptable level of false positives and false negatives will be acceptable in the deployed system. "The mental shift from chasing 100% accuracy with one good feature to optimizing an application-specific performance probability that is "good enough" will enable numerous new applications," says Paclik.

Companies Mentioned

Cognex

Natick, MA, USA

www.cognex.com

MVTec Software

Munich, Germany

www.mvtec.com

PR Sys Design

Delft, The Netherlands

www.perclass.com

Stemmer Imaging

Puchheim, Germany

www.stemmerimaging.com

About the Author

Andy Wilson

Founding Editor

Founding editor of Vision Systems Design. Industry authority and author of thousands of technical articles on image processing, machine vision, and computer science.

B.Sc., Warwick University

Tel: 603-891-9115

Fax: 603-891-9297