MEDICAL & PHARMACEUTICAL: Machine vision checks Braille code on drug packages

In October 2005, the European Commission (EC) mandated the use of Braille for pharmaceutical packaging on newly approved medicinal products. According to the EC directive, both the name and dosage of the medication must be embossed on each carton in Braille format. By using this format, a combination of up to six raised dots allows up to 64 alphanumeric characters and other symbols to be represented.

While this system is useful in providing valuable information to the visually impaired, it is a challenging task for system developers to inspect the Braille once embossed on the cartons. Indeed, even tiny faults in manufacturing can have dangerous consequences since just one incorrectly embossed dot can cause the visually impaired to mistakenly interpret dosage information.

To eliminate poorly embossed cartons from reaching the consumer, pharmaceutical packaging companies must now implement thorough quality assurance measures to inspect Braille. However, these 0.1–0.2-mm-high dots are indiscernible to untrained fingertips and visual inspection alone cannot verify whether the raised dots can be identified by touch.

Because of this, packaging companies often employ mechanical inspection systems that assess the tactile quality of a Braille dot by measuring its height with micrometer calipers. This method is time consuming and may be inaccurate since the calipers must directly contact the dots. Alternative solutions such as using visually impaired quality assurance personnel to inspect the Braille characters can be used but have the additional disadvantage that test results cannot be adequately documented.

To overcome these obstacles, in-situ (Munich, Germany; www.dotscan.de) has developed a machine-vision inspection system known as DotScan that uses a shape-from-shading technique to evaluate the Braille dot patterns. In this type of technique, the recovery of the shape of each Braille dot must be computed by analyzing gradual shading variations of captured gray-level images. A number of different techniques exist to perform shape-from-shading, most of which are described by Ruo Zhang and his colleagues at the University of Central Florida (Orlando, FL, USA; www.cs.ucf.edu) in their paper entitled “Shape from Shading: A Survey” (see www.cs.ucf.edu/~vision/papers/shah/99/ZTCS99.pdf).

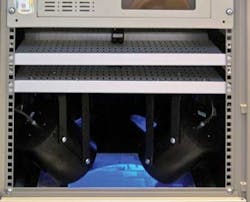

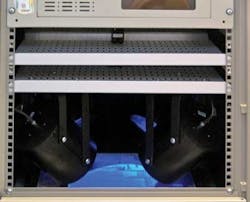

In such shape-from-shading techniques, it is very important for the light source used to be well defined. In the system developed by in-situ, embossed Braille cartons are inspected in a flattened form before they are folded and pasted together. After positioning these flattened boxes in the unit, four blue LED telecentric light sources above the object illuminate the carton over 150 × 75 mm from four directions (see Fig. 1). Since this telecentric light uniformly illuminates the carton, the 3-D shape of a raised dot can be accurately derived from its shading pattern. “Because the blue LED light has a shorter wavelength than red or white light, its higher frequency also results in a more accurate image when reflected light is captured,” says Rainer Obergrußberger, managing director of in-situ.

As each carton is individually illuminated from four different directions, the reflected light is captured using a 1.3-Mpixel UI-1540SE-M USB uEye industrial camera from Imaging Development Systems (IDS; Obersulm, Germany; www.ids-imaging.com). Because cartons can vary in color, reflected light may also vary from very light to very dark and it is important to capture high-dynamic-range images. Here again, many techniques can be used to accomplish this task (see “Dynamic Design,” Vision Systems Design, October 2009).

In the system designed by in-situ, multiple images of each carton are taken with different exposure times to increase the dynamic range of the captured image. This was accomplished by software-based triggering using the uEye API programming interface. These multiple exposures are then combined to form an image with a high dynamic range.

After these images from all four illumination angles are captured, they are transferred to a PC and shape information calculated using a shape-from-shading algorithm at a rate of 20 images per second. After the system checks whether the raised dots have the correct shape, the DotScan software identifies characters and words from the recognized Braille code and compares them to the manufacturer’s specification (see Fig. 2). These data are then used to perform a pass/fail analysis.

Interestingly, no government legislation similar to that of Europe is currently proposed in the United States or Canada. However, to satisfy the needs of the visually impaired in North America, the International Association of Diecutting and Diemaking (IADD; Crystal Lake, IL, USA; www.iadd.org) has created “Can-Am Braille,” a set of guidelines and recommendations for the use of Braille on packaging.

The IADD worked in conjunction with the Braille Authority of North America (BANA) to develop the standard, whose official release was in May 2009. Apparently, it was felt that such a proactive approach on the part of industry to develop and implement its own standard would be a way of reducing or even eliminating legislative intervention.

More Vision Systems Issue Articles