The Nature Conservancy Brings Cameras, AI to Invasive Species Prevention

The Nature Conservancy, a global environmental nonprofit, has added remote cameras and AI in to its effort to protect Santa Cruz Island from rats.

Santa Cruz Island, located off the Santa Barbara Coast in Southern California, is the largest of California’s Channel Islands chain and is owned by the Nature Conservancy (Arlington, VA, USA) and the U.S. Park Service. Accessible only by boat, its rugged, pristine, topography and extensive, unique biodiversity are major draws for nature enthusiasts; some 30,000 visitors visit the island each year, according to the USPS.

But some visitors are absolutely unwelcome, say TNC officials.

Invasive species are serious threats to vulnerable, fragile ecosystems such as are found on islands. Indeed, islands represent 5% of the earth’s total land mass, but have experienced some 61% percent of recorded extinction events since the 15th century, according to the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (Paris, France). Over the years, TNC has removed a number of invasive animals from Santa Cruz Island, including feral cats, raccoons, feral pigs, and golden eagles.

Rats, however, are universally considered the most dangerous and destructive of all invasive species, says TNC software developer Nathan Rindlaub. Hardy, voracious, omnivorous, and opportunistic, rats will not only decimate the existing food supply for native species, but also will actually eat some native species. They are notorious disease vectors, capable of carrying germs and parasites that will annihilate other species. And they are prolific reproducers; one pair of rats can produce as many as 5,000 descendants in a single year.

See Related Content: UK Company Brings AI to Worldwide Conservation Efforts

In other words, if rats ever establish themselves on Santa Cruz Island, the resulting damage to the fragile ecosystem will be cataclysmic. Fortunately, notes Rindlaub, no rats have ever been found on Santa Cruz Island.

Challenges

Environmental protection groups such as TNC usually deploy camera traps – traditionally, multiple battery powered, motion-activated mounted cameras – to monitor wildlife species. However, the island is 96 square miles and mostly remote, rugged, and difficult to access. Because communication infrastructure is extremely limited, in the past, volunteers/staff had to physically travel by boat to the island, then hike long distances over difficult, treacherous terrain to perform maintenance and/or pull data from the cameras. Once data was retrieved, individual staff/volunteers had to examine and analyze every image. This was not only very expensive, says Rindlaub, but the time gap between a camera recording potentially important information and that information being transmitted, analyzed, and if necessary, acted upon by TNC staff/volunteers, was lengthy, sometimes taking as long as several months.

“If a pregnant rat stowed away on one of the boats and got onto the island, we would need to know right away—literally within hours—in order to mount a meaningful response,” Rindlaub says.

Modern Tools

TNC experts realized they needed real-time information in order to protect Santa Cruz Island. They purchased 30 new BuckEye (Athens, OH, USA) X80 BT wireless cameras. Equipped with solar powered batteries, which enables them to operate for 3-5 years on one battery cycle, each camera can transmit up to 8 kb/s of data via radio signal. The cameras can transmit images from camera to camera to an internet access point, and on to the Microsoft (Redmond, WA, USA) Azure cloud platform.

“We have a single digit number of points of internet connectivity on the island,” Rindlaub says. “By being able to transfer data down the line, we can get information we need in almost real time.”

But they also needed a way to parse and analyze that data quickly. To that end, Rindlaub worked with TNC to develop Animl, a cloud-based data management platform designed especially for working with camera trap data. Animl is not meant to replace human analysis completely, but rather to speed and organize the process. It is also not a “first pass” species identification software, but rather a modular AI platform that can be trained, integrated and used for analyzing and organizing data within smaller, narrower parameters.

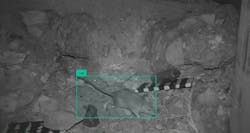

TNC uses another open-source, cloud-based platform, Microsoft (Redmond, WA, USA) Mega Detector, for first pass identification, Rindlaub says. Mega Detector, widely used by environmental protection groups around the world, has been trained on literally all available open-source camera trap imagery, is especially good at identifying people, vehicles, and animals and localizing them within an image by drawing a bounding box around the object of interest within the image.

“Being able to apply Mega Detector across the board to your images immediately cuts a lot of empty images—it can easily be 40 % of your images you now don’t have to review at all,” Rindlaub says.

Once the images are processed with Mega Detector, TNC volunteers/staff use Animl to further organize and prioritize analysis of all the remaining images depicting animals, based on AI models trained with much more localized images, Rindlaub says.

“We built Animl to support the development and integration of much smaller classifiers that are much narrower, limited in scope in terms of what species they predict and what they do well,” Rindlaub says. “We focused on ensuring that Animl was designed in a way that it’s really easy to deploy these new smaller classifiers and then configure customizable sequences of the models being invoked.”

For example, imagery from sub-Saharan Africa is not going to be useful in monitoring camera traps deployed off the coast of Southern California. However, Animl is trained using much more localized, specific images, in this case, species associated with California, Santa Cruz, and especially, rats.

Santa Cruz does have an indigenous deer mouse species, which are frequently identified in the camera trap images. If Animl detects something that needs further investigation, such as a rodent, then it can send an email alert or a text to TNC staff for further scrutiny and action.

About the Author

Jim Tatum

Senior Editor

VSD Senior Editor Jim Tatum has more than 25 years experience in print and digital journalism, covering business/industry/economic development issues, regional and local government/regulatory issues, and more. In 2019, he transitioned from newspapers to business media full time, joining VSD in 2023.